I wanted to belong — but I didn’t want to dress like everyone else.

Down Eastern Avenue, I passed television repair shops thick with dust; pawnshops, biker bars; a Taco Bell. In 1990s southeast Los Angeles, this is what people wore: teased bangs; discount jeans; T-shirts with kittens and phrases in puffy letters: “Someone in California Loves Me”; Payless tennis shoes that held up for a year (or two, with luck); Jordans from the swap meet (or occasionally, Foot Locker); white leather LA Gears with pink piping. I wore these things and fit in. My friends didn’t trip or make fun of me because that’s what we all wore: a uniform for nerds and regular kids. This was cool. I was a nerd but I was a regular kid because my family didn’t have enough money to set me apart. But after Luisa sashayed into my science class, the possibilities for what I could wear forever changed. Actually, it was also Town & Country’s fault. And of course, I can’t forget Amá.

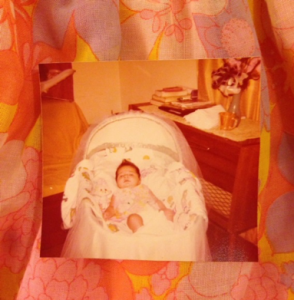

Amá, the second oldest of 12. She made my first dress: a sleeveless, empire waist in gauzy cotton. The flowers were printed in psychedelic oranges, muted yellows, and pink lilies, dahlias, asters. I had been hers for one whole month. The lining was light pink taffeta.

The author in a dress made exclusively for her. Photo: Vertiz family archive.

A dashing eighth grader, Luisa pranced around our middle school calling everyone “dear” like British ladies on TV. She wore orangey-red lipstick, black cardigans, and listened to bands of boys who wore eyeliner.

Like everyone else in Bell Gardens, the rustbelt of L.A., Luisa ate free lunch at school, but her older sisters had mall jobs. They brought home denim jackets and black penny loafers, which no one wore. Luisa’s clothes and speech made her stand out in a crowd of tall bangs.

During lunch, Luisa walked with by her friends. “Hello, my dears!” she would chirp. The yellow cheese quesadilla became suddenly boring. Our solidly gelled bangs followed Luisa and her friends as they walked away, but not for too long. Staring was for weirdos. I kept stealing glances of Luisa’s new V-neck sweater. My brain began secret calculations. What was in my house that could equal her style? White collared shirts, black pants, cardigans, V-neck sweaters.

Dad had several white collared shirts he didn’t wear anymore. A V-neck sweater? I saw one at the Price Club that maybe Amá would buy if I asked. My hair was shoulder length and brown — and! — my bangs weren’t too tall. If Luisa was from the same place, then I could still belong to where I was from, but look different. Special, even.

When I got home I locked myself in the family bedroom and tried on Amá’s copper lipstick. Not quite mod, but at least grown up. At the Price Club that Sunday, I asked Amá if I could have a fuzzy a deep V-neck white sweater made from wispy yarn.

In the aisle of the bulk book nuts, I saw my fashion future. I’m no Luisa, but this is good enough, I thought. It’s almost the same.

An ad in my first Town & Country, December, 1989.

Around then, Town & Country dropped into my lap. A mail offer came for almost-free magazine subscriptions: one year for a handful of dollars. I’d been ordering through the mail since Dad had taught me to fill out money orders and rent receipts. So I didn’t hesitate to send for fashion a magazine. (You might be wondering about how much money we actually had and what “poor” meant to my family. This assumes that you can only get fine things at a high price, but here is the heart and truth: the amount of money you have does not always determine your ability to have beautiful things or make them yourself. Also, Dad made enough money to give me a domingo every couple of weeks, which Amá enforced, no, she made me collect it. “Ask your Dad for your domingo! Otherwise he’s going to waste it on his vieja in Tecate.” There I went and got my magazine cash.) At the paycheck cashing place I made a money order out to the magazine and sent off a request for my future self.

Everywhere on Eastern Avenue, there were other girls like me— in no-name jeans, getting to school or home on foot, or however we could. Even though we looked alike, I already felt apart. A boy wrote this in my yearbook: “I hope to have you in one of my classes but I guess I won’t. You’re smarter and you’ll go to a better class.” These words felt good: you are better, smarter, what teachers and schools want you to be. But later as I got older, it was more like being a traitor. If I was smarter and I looked the part, then I’d be leaving everyone else to go fend for themselves.

You have to know that, within a 15-mile radius from my home, there were no bookstores or drug stores that sold (or currently sell) Town & Country. Still, there is nothing strange about a Mexican-American girl who lived by the freeway and wanted to see what was inside of a Town & Country. The cover photo was just like all the television shows I’d ever watched: a pouty, rich, light-skinned, thin woman dripping in diamonds. Mexican actors like Lucia Mendez and Veronica Castro taught me to daydream about condos overlooking the Caribbean, to want long dresses that trailed behind me, catching the wind.

Then the first issue came.

Locked in my family’s bedroom after school, I had my very own fashion magazine. A lippy woman adorned the cover crowned in a bouquet of red tulips. The pricey perfume samples on every other page were intoxicating—this is what beauty smells like. When I got more of them, Amá and I would cut them out and dab them on our wrists. But, where were the fashion spreads?

The afternoon sun burned through the window. But no matter how many pages I turned, all I saw were wedding snapshots of white people from Connecticut. They were no models. There they were in poufy-sleeved gowns at hospital galas (did that mean a kind of party or a kind of apple?). At the end of the 150-page tome there was an “Exclusive Directory of Outstanding Medical Specialists.” I flipped more pages until I found myself drawn to the ads.

Maybe it was the heat, but I swooned for Ralph Lauren’s wing-tips and riding boots. Country leather velvet wingtips? Yes! It all made sense: Amá had ridden horses as a girl. Somewhere in Mexico there were photos to prove it: Amá stood with her sisters and mother next to a burgundy colored horse, a cerulean sky behind them.

I let my longing set in: the delicious gazing, the wishing, the daydreaming of me somewhere in the country on a fancy rancho instead of in seventh grade, sitting on a hot-ass comforter. I ignored Amá’s rancheras and my brother’s cartoons playing loud in the rooms next door. My family’s king-sized bed was getting too warm to sit on. And with no significant fashion spreads, I lost my patience with T&C.

Amá asked to see the precious magazine. She opened it to a page featuring earrings shaped like Pegasus wings in black onyx and diamonds.

“Those are nice mija, but where would you wear them?” she said. Not to the eighth grade day dance at Bell Gardens Intermediate where I was headed the next year. “Some cholo might pop out of nowhere and take them.” But I hadn’t bumped into any cholos at school; they were not the gross older men ogling me on my way to school. I bet cholos had higher standards.

Diamonds, for sure, are not practical. Ralph Lauren made his mark on my penchant for plaid and velvet blazers, but it was not enough to make the magazine’s blue-blood social events interesting. I stopped looking through Town & Country to see if maybe I was in there.

Then my muse Luisa let me down. It was during sex ed. In a darkened bungalow at school, about 40 of us were discussing the qualities we liked in boys: cute, smart, polite.

“I like boys who have good dentures,” said Luisa.

Dentures are fake teeth, I thought. Even I know that and I don’t have grandparents (alive or that like me). I must have made the worst fuchi face — how could she not know the difference? No one told me being smart would make me a judgmental asshole.

Luckily, our teacher was more thoughtful and didn’t make Luisa feel like an idiot for not knowing the right word. She just clarified that Luisa meant “nice teeth,” not fake ones. But what she said told me that maybe I didn’t want to be exactly like Luisa; I turned my body away from her and faced her friend Claudia instead. She was wearing a leather jacket and a striped shirt from the Gap. She liked The Cure and wore whatever she wanted. Maybe I could be like her instead. I had to keep looking.

Back at home, Amá gasped at the T&C prices next to the jewelry, if it listed a number at all. “You want these, mija? Maybe they have some that look like that at the swap meet.”

“I know, huh?” I said, agreeing with Amá. “No, I want some that looks like that.” If I could see it, why couldn’t I have it?

“Bueno, Chata,” Amá said. “We’ll find a way to get them. Tu sabes arreglarte.” Styling. That’s what I needed, not diamonds or millions.

Rich people on TV and in T&C seemed wasteful. I was one step ahead of them: I came from resourcefulness. From Amá who made sweaters in Hidalgo, walking to and from work in leather pumps and wool pencil skirts. Amá of the white boat neck dress and bohemian black hair.

The author’s mother in 1969. Photo: Vertiz family archives.

Ten years later she immigrated to Los Angeles. She sent home half of her paycheck, somehow living off of and saving the rest of her cash. I came from resourceful, with a capital R.

I knew that prices didn’t inherently make anything better quality, but it sure did feel like it. Magazines smelled expensive, but I could get them for a few dollars. What was needed was resourcefulness, which was in my blood, but I couldn’t see it yet. The other thing you needed was the right attitude, which I practiced in the bedroom.

In the space between our beds and the closet, I modeled my version of Luisa-meets-Ralph Lauren-in LA— on four feet of a private runway. I dug into our cardboard box piled high with shoes: out came Amá’s black tasseled loafers that her sister Maria brought from Mexico the year before. They’d stopped fitting her, but they were perfect on me. I found Dad’s old ties and collared shirts. Amá was wearing cotton jersey knits now, not her polyester, embroidered blouses from the 80s so I grabbed those too and tried them on. This way, then, that way.

I liked one outfit best and added a pin: a gold-plated fly with glass rubies for eyes. This can work. It turned out nerds like me have what they need in their family’s closet.

You just have to look.

The author posing at Bell Gardens Intermediate. Photo: Vertiz family archive.

***

What does genre mean to you and how does it build/unbuild your work?

Cherrie Moraga told me, “Write down the stories that come to you. Worry about the genre later.” I was taking a play writing class with her, but I knew that by genre she also meant film, one-woman shows, essays, poems, and fragments. If it weren’t for her writings which thread theory, social justice, and her mother’s stories, I would not have had a way to articulate my life. And so, I go in story first, and the vessel(s) later, and if I follow the story long enough, the genre, the tense, the shape always changes. I’m taking apart stories and time inside them because linearity doesn’t serve the way I (re)experience life. Grief works this way, and joy too.

But of course, stories repeat. May we keep articulating what’s true for us in ways we’ve not yet imagined.

***

VICKIE VÉRTIZ is a writer from Bell Gardens, the rust belt of Los Angeles. Her work can be found in the New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Nepantla, among other publications. Her collection of poetry, Palm Frond with Its Throat Cut, was selected by the University of Arizona Press, Camino del Sol series for publication in September 2017. Vickie is also a VONA and Macondo Fellow who teaches writing and has read her work in Mexico City, France, Japan, and throughout the United States. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter @vickievertiz.