Statue of NFL Hall of Fame inductee Jim Brown (Photo courtesy of the author).

There are some sports moments so instantly iconic—feats of athleticism that change the trajectory of a game or a series or an entire season—that they take their rightful place in history under a single proper noun. The Drive. The Fumble. The Shot. The Decision. Even people who hate sports might recognize one of these mononymic events from the photograph that helped immortalize legendary outfielder Willie Mays: the Say Hey Kid, jersey number square to the camera and glove outstretched in anticipation of The Catch.

What most people, maybe even most sports fans, don’t realize is that every single one of these instant classics has come at the expense of a Cleveland team.

Cleveland, a place I’ve never lived but where my dad spent most of his childhood, is one of the most beleaguered cities in all of professional sports. When the Cavaliers defeated the Golden State Warriors in the 2016 NBA Finals, they gave the city its first pro championship—in any sport—in over half a century. The recently renamed Guardians now have the longest World Series drought in baseball, after giving up a down-to-the-wire Series in Game 7 to the former longest-term losers, the Chicago Cubs. If there’s a bone-headed, heartbreaking, infuriating, or inventive way to snatch last-minute defeat from the palms of victory, especially in an important game, a Cleveland team will find it. In his assessment of the city’s collective calamities, sports analyst Bill Simmons said it best: “God hates Cleveland.”1

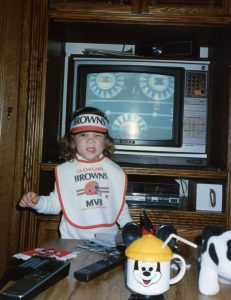

Of the city’s three primary teams, the Browns are the sorriest. They’ve never won a Super Bowl, but that’s a tough feat to pull off when you’ve never even been to a Super Bowl. Over a two-year stretch, Disney released more Star Wars movies (three) than the Browns won games (one). Other teams’ ESPN highlight reels frequently feature Browns players toppling ineffectually in the background, as if they’re choreographing a dance to a version of “Yakkety Sax” that only they can hear. I own a pair of T-shirts that read I survived the 635-day losing streak and I survived the 18-year playoff drought because these, along with the 2017 “perfect” 0-16 season, are two of the team’s most recent records. In fact, for three years in the ’90s—a formative period of my youth—there weren’t any Browns at all, because then-owner Art Modell moved the team to Baltimore, where they became the Ravens and promptly won the Super Bowl. The last time the Browns won a championship, the AFL and NFL hadn’t yet merged and my dad was a recent immigrant to the city nicknamed the Mistake by the Lake.

To be a Browns fans, then, is to live a life of frustration, wild optimism, irritation, faux indifference, jealousy, wry deprecation, and despair, all of it self-inflicted. To live a life of a writer is much the same. Over the eighteen years that I’ve been publishing work in various capacities, I’ve learned plenty from courses and craft books that dwell on plot, character-development, and lyrical sentences. But when it comes to the business side of things, I’ve learned the most from my thirty-six years as a fan of the most hapless professional football franchise on the face of the planet. If you want to understand the writer’s life—the avalanche of regular rejections, the days of grinding work with little reward, the recalibration of what constitutes success, and the unquenchable hope that a book with your name on the cover will eventually have pride of place on your shelf… Well, have you considered rooting for the Browns?

Lesson 1: It’s Okay to Start Over

Sometimes I think the Browns stenciled that famous writing advice, kill your darlings, on the walls of their front office. They’ve hit the reset button on their coaching staff more times than a gamer reloading an RPG, firing and hiring a new head coach approximately every two years. After the NFL permitted Cleveland to reinstate the Browns in 1999, the team proceeded to blow through thirty starting quarterbacks in less than two decades. For comparison, over the same period, the New England Patriots—a team I loathe the way Indiana Jones hates snakes—mostly started that one guy named Tom Brady and won a gazillion Super Bowls. They also had only one coach: Bill Belichick, who, incidentally, was fired from the Browns’ head coaching job in 19952.

The front office is probably a little too quick to jettison components that aren’t working, but there’s something admirable in how fully they let go of old plans to focus wholeheartedly on their newest configuration. Three years ago, after querying a manuscript that received full requests from agents but no offers of representation, I abandoned that novel to start work on a new one. I’d spent eight years on that previous project—sixteen times as long as the Browns have spent with their average starting QB—and friends wanted to know how I could set it aside so easily. The answer was simple: the old novel wasn’t working, and I couldn’t figure out how to fix it. Rather than attempting to develop a stagnant manuscript, I needed to start fresh and rebuild—kind of like replacing Kevin Hogan with Tyrod Taylor and then Baker Mayfield.

Lesson 2: Sometimes No One Cares

From 2016 to the middle of the 2018 season, the Browns stretched all three words in the phrase professional football team to a breaking point. They were so incompetent that Congressman Ted Lieu (D-CA), himself an immigrant to Cleveland and an ardent Browns fan, frequently compared them to the Trump administration. After the team’s disastrous, winless 2017, fans threw an impromptu “perfect season” parade, in which one reveler, dressed in a full-body T. Rex costume, held a sign that read Number one fan last time the Browns were good. Morale was so bad that the team started offering amusement park tickets at home games to entice fans into showing up.

During that infamous 635-day losing streak, I realized that waiting for the Browns to finally notch a victory was like waiting for an agent to respond to my manuscript queries. In both situations, I felt a lot of futile aggravation and impatience, mixed with the sense that maybe my energy would be better focused on something else. The main difference between the Browns’ rough 2017 and a rough writing/querying day was that no one was offering me tickets to Cedar Point just for showing up at my desk and refreshing my email.

In one of our long, loss-filled Decembers, I asked my dad, by way of small talk, “How ’bout those Browns?”

“Who cares?” he responded. He said it with the kind of vehemence that showed he still very much cared, despite the increasingly real possibility that the Browns would never, ever win another game in either of our lifetimes. But the phrase resonated with the struggling writer part of myself. No one cared about my manuscript except for me—and that was okay. In fact, it was liberating. So what if I stopped trying to perfect my queries for a few days and tried drafting something fun? So what if the Browns had stopped seeing their season as a series of competitions and started playing football as a type of bizarre performance art? If no one’s reading—or watching—anyway, who cares what you’re doing at the privacy of your own desk or in your empty stadium? And sometimes, removing all that internal pressure moves writers (and football teams) in the right direction. Of course, for the Browns this has involved some starting over, too (see Lesson 1), but that’s not always a bad thing, as long as you know which projects to stick with. I started writing this essay because I needed a break from my current novel manuscript, but I know that when I go back to it, I’ll have a renewed sense of purpose and freedom from perfectionist constraints…at least temporarily.

Lesson 3: Success Is Not Straightforward

The Browns haven’t been bargain-basement bad for the entirety of the last fifty years. In the late ’80s, they were strong enough contenders to make it all the way to the AFC Championship—the playoff game that immediately precedes the Super Bowl—two years in a row. The Browns were leading in the fourth quarter of the first match-up, but then opposing quarterback John Elway led the Denver Broncos ninety-eight yards down the field to tie the game in its final minutes. The Broncos would go on to win that game in overtime, ending the Browns’ season and cementing The Drive into sports lore. I’m sure if you told fans that almost the exact same thing would happen the very next year—losing the AFC Championship to the Broncos due to a last-minute error that’s now known simply as The Fumble—we wouldn’t have believed you. And if you’d told us that, in another seven years, the team would cease to exist, we wouldn’t have believed that, either. After all, the Browns had had a dominant decade (relatively speaking)!

Likewise, if you’d told my twenty-five-year-old self that I would be at least thirty-seven—and probably older, at the rate things are going—before I published my first book-length work, I would’ve scoffed. I had twice won my college’s annual creative writing award, including once as a freshman, and I was applying to MFA programs. I’d already written one novel that I’d attempted querying. I thought that I’d spend the next two years writing another, better manuscript, for which I’d snag an agent and then a publishing deal.

That didn’t happen. For a few years after graduating from my low-residency program, my writing career was looking up. I was getting almost-but-not-quite personal rejections from top-tier literary magazines, and I thought it was just a matter of time before I broke through. However, like those late ’80s Browns teams that never made it to the Super Bowl, I never cracked those markets, and I ran out of short stories to send them. Instead, I turned back to writing novels, which I sensed could help me build a more solid long-term career. To an outside observer, I might look like I’ve been suffering from my own 18-year playoff drought, but I’ve been working hard the whole time—even if I don’t have a long list of publications to show for it.

Lesson 4: You May Not Ever Make It to the Big-Time

There is no guarantee that the Browns will win a Super Bowl in my lifetime. There is also no guarantee that I will ever publish a book, let alone win an Edgar or a National Book Award or a Pulitzer. As much as I want all of these things to happen, and as hard as I work at my writing—and at exhorting the Browns through the TV—I know that these things are beyond my control, and that they’re less likely to happen the older I get. I root for the Browns because my family (mostly) loves the Browns and football is part of how we enjoy our time together. I write because I love to write, with a deep, abiding passion that surpasses even my die-hard love for sports. Accolades and Super Bowls are pleasant bonuses, but they’re not why I write every day or voluntarily wear safety-cone orange on Sundays3. (But if you’re listening, God-who-hates-Cleveland, a Super Bowl and an Edgar would be very nice.)

Lesson 5: And Yet, Hope Springs Eternal

After the Browns moved to Baltimore, or so the legend goes, Cleveland fans continued to gather in the stadium’s parking lot every Sunday to tailgate. It didn’t matter that the team didn’t exist anymore, and that Cleveland Muni would soon be demolished. The Browns would be back, those fans knew in their hearts, and in the meantime, loyal Brownies across the nation would keep the spirit of the Dawg Pound alive.

After the Browns moved to Baltimore, or so the legend goes, Cleveland fans continued to gather in the stadium’s parking lot every Sunday to tailgate. It didn’t matter that the team didn’t exist anymore, and that Cleveland Muni would soon be demolished. The Browns would be back, those fans knew in their hearts, and in the meantime, loyal Brownies across the nation would keep the spirit of the Dawg Pound alive.

Now, for the majority of football fans who aren’t Browns devotees, this possibly apocryphal tailgating tale illustrates why Cleveland fans are often objects of scorn and pity. To outsiders, we’re playing an unrealistic game of what-if built on pure faith in a team with, at best, an unproven track record—a process that sounds an awful lot like writing a first novel and trying to get it published. It’s incomprehensible why any otherwise rational adult would emotionally yoke themselves to The Factory of Sadness. Several weekends ago, when I proudly wore my orange hoodie and Sundays are for the Dawgs T-shirt to a coffee shop writing session, some nearby bros decided to tease me a little. “Who the hell roots for the Browns?” they joked. “Oh wait, never mind—we found one!”

For the first time in decades, however, things are looking up for the Brownies. Last season, the team earned its first playoff victory since January 1995 (which may not seem like such a long time ago until I tell you that back then I was eight, and am now almost 36). So far this season, they’ve lost almost as many games as they’ve won, but the losses have been close ones, for the most part. For Cleveland fans, that’s a very positive sign: after all, five victories this season is four victories more than the team achieved in all of 2016 and 2017 combined!

So, no, I may never publish a book and the Browns may never win a Super Bowl and no one may ever care about my writing except for me. Yet, I still hope. I write every day. I’m not sure what the writing equivalent of those mid-’90s Dawg Pound tailgaters is—I’m not sure I want to know the writing version of grown men in Browns jerseys and latex bulldog masks, barking at opponents4—but there’s a spirit inside of me that expects that most days at my desk will produce some kind of small victory. When I mark up a manuscript draft with revision notes, I’m kindling the faith that it will grow into a novel worth publishing. After all, if the Browns can come back to Cleveland, all sorts of miracles could happen.

“If we ever win the Super Bowl,” I told the bros, “you know it’s going to be so damn sweet.”

And then I went back to writing.

Footnotes

1For the Biblically-minded, there’s some evidence for this theory beyond the abysmal team results: In 1969, Cleveland’s main river, the Cuyahoga, caught fire and burned for several days, and in 2007, an apparent plague of locusts descended upon the American League Championship Series, causing the visiting New York Yankees to bellyache about the playing conditions.

2Yes, the Browns are so bad that one of the winningest coaches in football history couldn’t lead them to a solid record.

3Speaking of awful, the Browns’ official team colors are brown and orange. This means that, every Sunday in autumn, a sizeable portion of the city of Cleveland dresses up like your grandmother’s living room from the 1970s.

4No, I’m not making this up. Since the Dawg Pound’s formation in 1985, the team has had to officially ban dog food in the stadium, as Dawg Pound members have thrown Milk Bones, eggs, batteries, and other projectiles at opposing teams.

Rachael Warecki is originally from Los Angeles, where she currently resides, but harbors an oft-painful love for Ohio sports. She has attended residencies at MacDowell and the Ragdale Foundation and holds an MFA in fiction from Antioch University Los Angeles. Her mystery novel-in-progress, The Split Decision, was a finalist in the 2019 CRAFT First Chapters Contest, and her short work has received the Tiferet Prize, semifinalist honors in the American Short(er) Fiction Contest and the Boulevard Creative Nonfiction Contest, and a Best of the Net nomination.